Snake: Snake.

Ocelot: No. Not that name. You're not a Snake and I'm not an Ocelot. We're men with names.

-Major Ocelot and Naked Snake, Metal Gear Solid 3: Subsistence (2006)

What’s in a name, indeed. That question is at the very core of this week’s question. Since people seldom use their full, real names online, often a name, especially in an online community, is the only way to know if you’re talking to the same people week after week. In time, people tend to recognize people by name the same way they’d recognize people they meet everyday. Friendships, or even closer relationships are formed, on the basis that the person behind the name is the same person you’ve been talking to for weeks, perhaps months on end.

There are many areas in which such relationships and the names they’re based on can be found. Be it in online communities like forums, chat programs like IRC or MSN, or even the humble Email, there are many, many places were such exchanges, and therefore the potential for identity theft exist.

Email, for instance, has become a vehicle for one of the more insidious forms of identity theft. This would be phishing, defined as a criminal activity utilizing social engineering methods. (Phishing, n.d.) How does phishing work? By getting inside your head.

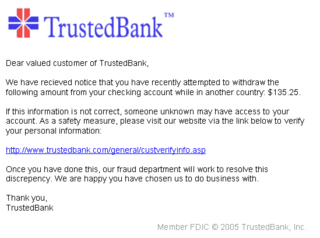

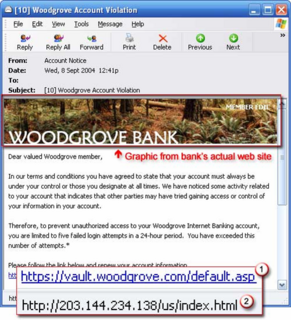

Above are two examples of phishing emails, both bank-related. Now, for the getting-inside-your-head bit. Granted the one above is just an example, but imagine that the logos have been replaced by DBS ones, and you’re already halfway there. The one below, shown during Mr. Ian Loe’s presentation, is significantly more realistic. How does it get inside your head? By pretending to be from an institution you know and trust to handle your money, it then asks you for the key to your bank account. And it’s apparently quite effective, too. According to one report, identity theft cost U.S. citizens US$52.6 billion in 2004. (Hooked on Phishing, 2005)

This works for a couple of reasons. Firstly, as mentioned above, the email appears to come from a trustworthy source, and secondly, it appears to be asking for sensitive information for a legitimate reason, such as an expired account or a database update. Thirdly, the email is done up very well, and often looks thoroughly authentic. Finally, the user may already have received emails from the company before (albeit for totally different reasons), and is used to simply complying. And so, passwords, ID numbers, credit card numbers, and all manner of personal data is stolen on an almost daily basis.

Another, similar form of such identity theft is pharming. However, pharming is an evolved version of phishing in that large groups of people can be affected, even when typing in the proper URL. This occurs when a company DNS server is compromised, redirecting traffic attempting to visit a legitimate website to the hackers’, thus serving sensitive personal data on a silver platter. (Pharming, n.d.) This is turns most conceptions of identity theft on its head, since when most people think of identity theft, they think of someone stealing their name or their social security number, and making transactions in their name or withdrawing their cash. As far as pharming is concerned, however, it actually works by diverting web traffic attempting to enter a legitimate company server to the hacker’s, thus allowing them to steal a large number of passwords or data in one fell swoop.

Of course, this does not mean we are all doomed to give our money to crooks who might be working out of their bedrooms in Russia or Czechoslovakia. By utilizing common sense and some equally common utilities available to us (e.g. online certificates), or some of the precautions listed here and here, online transactions can be as safe as face-to-face transactions, or perhaps even more so. After all, you don’t really know what that waiter’s doing with your Visa, do you?

___________________________________________________________

References:

Opening quote taken from Metal Gear Solid 3: Subsistence. Produced by Hideo Kojima, 2006, and published by Konami Corporation, for the Sony Playstation 2 console.

Phishing. (n.d.). Retrieved February 21st, 2007 from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phishing

Hooked on Phishing (2005). Retrieved February 21st, 2007, from http://www.forbes.com/business/2005/04/29/cz_0429oxan_identitytheft.html

Pharming. (n.d.) Retrieved February 21st, 2007, from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/pharming