Copyright is, and rightly so, an extremely touchy subject. In one corner, we have the public, and in the other, the various record/software companies and their tag-team partner, the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA).

The RIAA’s battle with file-sharing networks dates all the way back to 1998, when then-president Hilary Rosen, an outspoken critic of peer-to-peer (P2P) networks, directed a legal campaign aimed at stamping out illegal file-sharing worldwide, with an eye towards stopping people from sharing copyrighted music. The RIAA claims that such sharing costs the music industry $4.2 billion worldwide. (Efforts against file sharing, RIAA, n.d.) How do they explain this claim? According to them,

“Internet distribution of music, without the consent of the owner of the copyright to that music, harms the careers of current and future artists, both because record companies would have fewer sales, and also because musicians, singers, songwriters and producers depend heavily on royalties and fees gained from their music.” (Efforts against file sharing, RIAA, n.d.)

This is correct, insofar that content owners’ permission should rightfully be obtained. However, as for it harming the careers of current and future artists? That’s a little off the mark. There are those who believe, with some justification, that far from hurting an artiste’s career, having songs shared actually stimulates demand. Let’s talk about the radio for a second here. Is it out of the realm of possibility that you could listen to a song on the radio and say to yourself, “Hey, this song is pretty cool… Think I’ll pick up the CD and listen to the other songs by this band.” Same thing with P2P sharing. You could download a song from the Internet, enjoy it, and decide to check out what else the band is offering. This actually happened to the UK band Radiohead in July 2000, when

“tracks from English rock band Radiohead's album Kid A found their way to Napster three months before the CD's release. Unlike Madonna, Dr. Dre or Metallica, Radiohead had never hit the top 20 in the US. Furthermore, Kid A was an experimental album without any singles, and received almost no radio airplay. By the time of the record's release, the album was estimated to have been downloaded for free by millions of people worldwide, yet in October 2000 Kid A captured the number one spot on the Billboard 200 sales chart in its debut week. According to Richard Menta of MP3 Newswire, the effect of Napster in this instance was isolated from other elements that could be credited for driving sales, and the album's unexpected success was proof that Napster was a good promotional tool for music.” (Promotional power, Napster, n.d.)

Granted that this doesn’t happen all the time, but it is evidence that the untold damage to Radiohead’s career that the RIAA was predicting didn’t happen. Nevertheless, we must acknowledge that music piracy is a growing problem, and fairly speaking, the artistes are entitled to recompense for their work.

However, lawsuits are not the way. The Digital Rights Management (DRM) that Bertelsmann (the record companies BMG, Arista and RCA) placed on a large number of their CDs is also not the way. Compounding the error was Sony BMG, whose rootkit was installed on a PC without the user’s knowledge. Both were supposedly put in to prevent people from copying the CD, but not only could they be bypassed by simply holding down the shift key, they also left a computer vulnerable to certain security exploits. In addition, certain CD players, like those in a car or certain PCs, were often unable to play the CDs at all. (DRM and Audio CDs, Digital Rights Management, n.d.)

This resulted in a massive backlash, especially for Sony, who were eventually forced to recall millions of CDs.

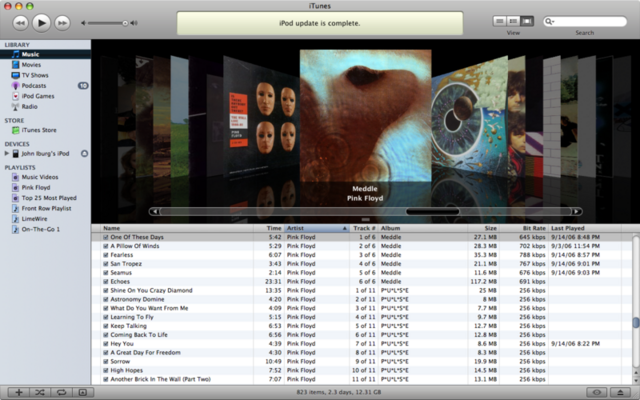

So how do we reconcile the music industry’s need for recompense and the public need for cheap, readily available music? The answer lies in the iTunes shop.

How so? On iTunes, songs go for US$0.99 per song, which at the current rate of 1.7 is about S$1.70. Now, if you were to break down the average CD by track, you would still come up to about $2 a track, but you’re also stuck with the songs you don’t really want or listen to. If, however, consumers were able to download only the songs they want, and pay a fair price for it, sales would take off rather quickly.

Of course, it’s not viable for the whole world to convert to iTunes. Aside from the fact that it’s not available in Singapore, not everybody will want to use iTunes. Hence, the solution would be for a local, or even a regional, online music store to cater to the local/regional market, offering the services iTunes is currently offering.

This would work for a number of reasons. Firstly, people are perfectly willing to pay for songs. This is evidenced by the fact that since opening on April 28, 2003, the iTunes store has sold over 2 billion songs worldwide (iTunes Store, n.d.). That’s in a little over three and a half years. Secondly, if security on such an online store is sufficiently tight, consumer confidence in it would take sales to an even higher level. In addition, on top of songs, the iTunes store also sells MTVs, movies, and TV shows (Video, iTunes, n.d.). A regional online store selling these products would be huge, as another big piracy issue, movies, would be addressed as well.

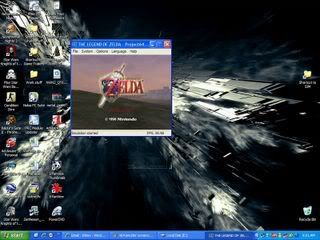

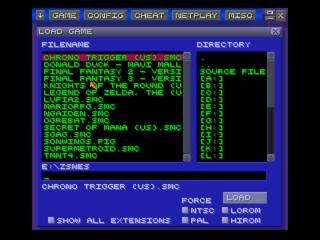

A similar issue was faced with console game emulators, which are readily available for download all over the Internet. Essentially, an emulator is a program which allows one to play console games on a PC, such as the old Super Nintendo Entertainment System (SNES), all the way up to the Playstation. Below you can see Sega Genesis, Nintendo 64, and SNES emulators, in that order.

At one time, console manfacturers attacked websites hosting such emulators, along with the ones hosting the ROMs or ISO images of the games, instead of the programmers of the emulators, as reverse engineering is protected by U.S. law (Legal Issues, Console Emulators, n.d.)

Interestingly enough, software companies have since begun to utilize emulators for themselves. The most recent example would be the Nintendo Wii, which comes packaged with a Virtual Console that allows users to download (for a fee) and play games from the NES, SNES, and Nintendo 64, along with titles from the Sega Genesis and Turbo-Grafx 16 systems. (Virtual Console, n.d.).

Thus, record companies should go the same route, and offer songs for download in the same manner, and for a reasonable price. People would buy it, the record companies make money, everybody wins.

___________________________________________________________

References:

Recording Industry Association of America, n.d. In Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 23:20, February 1, 2007, from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Riaa

Napster, n.d. In Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 23:20, February 1, 2007, from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Napster

Digital Rights Management. Retrieved 23:20, February 1, 2007, from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

iTunes Store, n.d. In Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 23:20, February 1, 2007, from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ITunes_Store

iTunes, n.d. In Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 23:20, February 1, 2007, from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ITunes

Console Emulators, n.d. In Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 23:20, February 1, 2007, from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

Virtual Console, n.d. In Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 23:20, February 1, 2007, from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

PVP Comic Strip taken from http://www.pvponline.com

iTunes Image taken from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 23:20, February 1, 2007, from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Image:ITunes_7_coverflow.png

1 comment:

Awesome-ness, you've actually covered a good range of topics, but still remain focused on finding a viable solution to managing fair use. Interesting use of iTunes and Wii's classic video game downloads as analogy. Full grades here.

Post a Comment